4 States of the ‘Cycle of Violence’ Study

Understanding the Four States of the 'Cycle of Violence' Study

Introduction

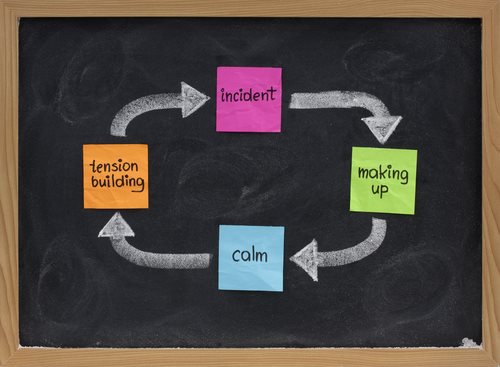

The 'Cycle of Violence' is a well-established concept in the field of psychology and criminology that seeks to explain the repetitive and escalating nature of domestic violence. This cycle, first introduced by psychologist Lenore Walker in the 1970s, has been instrumental in understanding the dynamics of abusive relationships and has guided interventions and policy decisions aimed at preventing and addressing domestic violence. In this article, we will delve into the four states of the 'Cycle of Violence' study, drawing upon government resources and related information to provide a comprehensive understanding of this critical concept.

1. Tension-Building Phase

The 'Cycle of Violence' begins with the tension-building phase, characterized by a growing sense of unease and tension between the abuser and the victim. During this phase, the abuser may display signs of irritability, anger, and frustration, often triggered by seemingly minor issues. The victim may feel as though they are walking on eggshells, attempting to avoid any actions or statements that could set off the abuser.

Government Resources: The U.S. Department of Justice, through its Office on Violence Against Women, provides extensive information and resources on domestic violence prevention and intervention. They emphasize the importance of recognizing early warning signs and behaviors, which align with the tension-building phase of the 'Cycle of Violence.'

2. Acute Battering Incident

The tension-building phase eventually leads to the second state of the cycle, the acute battering incident. In this state, the abuser's anger and aggression reach a boiling point, resulting in a violent outburst. This can involve physical, emotional, or sexual abuse directed towards the victim. The severity of the violence can vary widely, from relatively minor incidents to life-threatening attacks.

Government Resources: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States maintains a comprehensive database on intimate partner violence (IPV). Their research and publications shed light on the prevalence and consequences of acute battering incidents within the context of domestic violence.

📝 See Also

3. Honeymoon Phase

After the acute battering incident, there is often a period of relative calm and contrition known as the honeymoon phase. During this stage, the abuser may show remorse, apologize, and promise to change their behavior. They may shower the victim with affection and gifts, attempting to reconcile and restore the relationship.

Government Resources: The National Domestic Violence Hotline, funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, provides resources and support for domestic violence victims. Their materials discuss the complexities of abusive relationships, including the cyclical nature of violence and the honeymoon phase.

4. Tension-Building Phase Redux

Unfortunately, the honeymoon phase is typically short-lived. As time passes, the tension and unease begin to build once again, marking the return to the tension-building phase. This cycle continues, with the tension-building phase leading back to another acute battering incident, followed by another brief honeymoon phase, and so on.

Government Resources: The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), a landmark legislation in the United States, has been instrumental in addressing domestic violence. It has provided funding for research, prevention, and support services aimed at breaking the cycle of violence. The U.S. Department of Justice's Office on Violence Against Women administers VAWA grants and publishes reports on their impact.

Breaking the Cycle of Violence

Understanding the 'Cycle of Violence' is crucial for both victims and those working to combat domestic violence. It highlights the cyclical nature of abuse and explains why victims often struggle to leave abusive relationships. Government agencies, nonprofits, and advocacy groups have developed various strategies to break this cycle and support survivors.

1. Education and Awareness

Government resources, such as those provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and the CDC, emphasize the importance of educating the public about domestic violence. Awareness campaigns aim to help individuals recognize the signs of abuse and understand that they are not alone. Knowledge is a powerful tool in preventing and addressing domestic violence.

2. Support Services

Government-funded programs offer vital support services for victims of domestic violence. These services include shelters, counseling, legal aid, and hotlines like the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Ensuring that survivors have access to these resources is essential for their safety and recovery.

3. Legal Protections

Legislation like the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has significantly strengthened legal protections for domestic violence survivors. VAWA has enhanced law enforcement responses, improved access to protective orders, and increased funding for victim services. Government agencies work to enforce these laws and hold abusers accountable.

4. Rehabilitation and Counseling

Efforts are also made to address the root causes of abusive behavior. Some government-funded programs focus on rehabilitating offenders, providing counseling and therapy to help them change their behavior and break the cycle of violence.

5. Empowerment of Survivors

Empowering survivors to take control of their lives and make informed decisions is a key aspect of breaking the cycle of violence. Government resources and support networks aim to help survivors regain their independence and rebuild their lives.

Conclusion

The 'Cycle of Violence' study has been instrumental in our understanding of domestic violence, shedding light on the repetitive and escalating nature of abusive relationships. Government resources and initiatives play a crucial role in preventing and addressing domestic violence by providing education, support services, legal protections, rehabilitation programs, and empowerment for survivors. By breaking the cycle of violence, we can work towards creating safer, healthier communities where everyone can live free from fear and abuse.

What is the ‘Cycle of Violence’?

The ‘Cycle of Violence’ is a psychological ideology founded by Lenore Walker – a clinical psychologist considered to be amongst the pioneers of psychology with regard studies of domestic violence and abused women.

The Cycle of Violence serves to illustrate the methodology, process, and systematic manifestation of abusive relationships; this ideology not only outlines the events leading up to domestic violence cases, but also the itemization of the gradual unfolding of events resulting in domestic violence.

Upon understanding the Cycle of Violence, Dr. Walker had hoped to spread the results of her studies in order to provide assistance to individuals suffering from abusive relationships and situations; as a result, victims of domestic violence would be given the opportunity to remove themselves from harmful situations, but individuals would be given the tools to notice patterns within abusive situations.

The 4 Stages of the Cycle of Violence Study

Within the Cycle of Violence study, Dr. Walker cites the 4 stages of abuse and domestic violence; these stages range from the inception of domestic violence to the tragic and devastating aftereffects:

‘Tension Building’

The building – or rising - of tension is considered to be the first phase of the Cycle of Violence, which manifests itself through passive aggression, the facilitation of distance on the part of the abuser towards the abused partner, and the establishment of a nervous, tense, and agitated state within the romantic relationship - the ‘Tension’ phase results in a heightened sense of fear and anxiety on the part of the abused partner

‘The Incident’

The enactment of the abusive incident in question is considered to be the second phase of the Cycle of Violence, which is classified as the abusive action or expression manifesting itself; abuse taking place within the ‘incident’ phase can include spousal abuse that is physical, emotional, or sexual in nature - the ‘Incident’ phase results in the establishment of intimidation in order to facilitate the abuse taking place

‘Reconciliation’

The enactment of reconciliation undertaken by both individuals participatory within the abusive relationship is considered to be the third phase of the Cycle of Violence, which involves the abuser expressing remorse for their respective actions; in certain cases, the ‘Reconciliation’ phase may involve the abuser denying the abuse that had taken place; Dr. Walker cites that this denial may result in the proliferation of self-doubt and guilt within the abused partner

‘Calm’

The sense of calm and peace subsequent to the abusive incident is considered to be the fourth phase of the Cycle of Violence, which involves the period following the apology or expressed sense of remorse on the part of the abuser; typically, a sentiment of forgiveness or disregard for the prior abuse is not only implicit, but expected within the ‘Calm’ phase - the danger reported within the ‘Cycle of Violence’ study is primarily evident with regard to the repetitive nature innate within this cycle

Assistance for Victims of Domestic Violence

Upon the review of the Cycle of Violence, if any or all of the stages area applicable to you – or your current situation – through the involvement in current Domestic Violence cases or cases that have occurred in the past – you are encouraged to contact their local authorities or law enforcement department in order to report the details of the offense.

Despite the alarming rate of domestic violence, almost half of domestic violence abuses are not reported; remember - the opportunity to report Domestic Violence offenses in an anonymous fashion is also available to you upon contacting the National Domestic Violence Hotline through their 24-hour telephone number: (800) 799-7233.